Nenette Evans

(Bill’s wife)

The film is musically intriguing and sensitively crafted. Not soppy with just the right amount of honesty regarding his personal life.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

Debby Evans

(The subject of Waltz for Debby)

The film was a bull's eye at capturing as much as one can capture of someone's music, pain, and life story. My family is forever grateful to your outstanding work.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

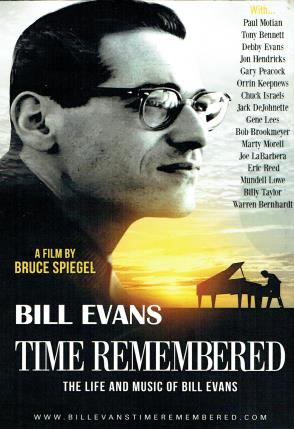

Bill Evans: Time Remembered The Life And Music Of Bill Evans

Peter Jurew

November 12, 2016

Eight years in the making, Bruce Spiegel's touching documentary on the life and music of the late, great, and mysterious pianist is a must-see for jazz history buffs, as well as for anyone who enjoys cool, impressionistic piano—the style Bill Evans pioneered beginning in the early 1950's and owned and expanded up to his death in 1980 at the age of 51. The categories are broad enough to include scores of listeners. Because isn't it true that, once one hears him—whether leading his brilliant trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian on Sunday At The Village Vanguard, or anchoring the celestial Miles Davis Kind Of Blue sextet—everyone digs Bill Evans?

What was it about the music this man made—or, more appropriately, what is it about the music—that makes it so compelling? Actually, just about everything: harmonic approach; technique and touch; authentic emotional content; strength and sensitivity. The music of Bill Evans still sounds fresh and contemporary and his influence on later generations of jazz pianists is immense and ongoing. Which raises another question: did we need a film to tell us what we already knew?

The answer, based on a recent viewing, is a resounding yes. There's much about Bill Evans that was, and is, a mystery, and the film goes into great detail to explore the facts of Evans's life while maintaining clear focus on the music. Spiegel lays the facts out chronologically, using old photos and stories from family, friends and associates both in and outside the business, as well as extant audio recordings of Evans himself that carries much poignancy throughout the film.

Born in 1929 into a Father Knows Best-type of suburban family in Plainfield, New Jersey, he was exposed to classical music ("all the Russians") and trained to the point where he was a "pretty good sight reader by the age of nine" (his description). He was gigging professionally at the tender age of 13, a driven music student at Southeastern Louisiana University, did a stint in U.S. Army bands, and by the mid-to-late 1950's was working in New York as an ace sideman with the likes of Art Farmer, George Russell, Charles Mingus, and Davis, among others. A prolific composer, Evans carried a pocket-sized music notebook with him at all times to capture ideas for tunes on-the-go—he wrote more than sixty originals, a few of which, such as his first major composition, "Waltz For Debby," and "Blue In Green," written for Kind of Blue, have become jazz standards.

The chronological structure Spiegel uses to frame the facts of Evans's life enables a deep exploration of the genesis and development of the pianist's musical ideas and the technique with which he expressed them. The commentary of former band mates and musical colleagues such as Motian, Jon Hendricks, Jack DeJohnette, Jim Hall, Billy Taylor, Bob Brookmeyer, the editor and lyricist Gene Lees, the producer Orrin Keepnews, Tony Bennett, Chuck Israels, Marty Morell, and others, bear witness to the arrival and full flowering of the Bill Evans we know, and also helps explain the darker side of Evans—touched by tragedy, afflicted by depression, addicted to opiates—the public did not see but could hear in his music. Contemporary jazz pianists, including Bill Charlap and Eric Reed, provide astute analysis of Evans's huge effect on later generations in terms of chordal harmonics and technique.

The portrait of Bill Evans drawn by Spiegel is a classic high-low, dark-light mix of a young man who arrived on the scene during a period of tremendously fertile creativity, populated by a vast array of musical talent, many of whom were plagued by the scourge of addiction; the young man was quickly recognized and soon made his mark—stylistically on his instrument and through powerful written compositions—enough to earn genuine modern jazz immortality while paying a heavy personal price in terms of wellness and relationships, not to mention longevity. By now, unfortunately, this Faustian bargain is familiar, the artist gaining glory at the expense of constant pain and compromise for family and friends, he himself struggling but finally unable to survive the realities inexorably imposed by his tortured all too human nature. Sadly, traces of this struggle remain in Evans's surviving spouse, Nennette, and son, Evan, neither of whom agreed to participate in the making of the film.

Also sad is the passing of the Evans cohorts who so enliven the fill, as Motian, Taylor, Lees, Keepnews, Brookmeyer and Hall are no longer with us.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

Bill Evans: Time Remembered (The Life and Music of Bill Evans)

Troy Dostert

March 7, 2017

In the opening segment of Bruce Spiegel's splendid Bill Evans documentary, Time Remembered, Evans explains in an early interview: "Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that all I must do is take care of the music. Even if I do it in a closet. And if I really do that, somebody's going to come and open the door of the closet and say, 'Hey, we're looking for you.'" It's an assertion both typical of Evans's self-effacement and also an ironic understatement, as there have been very few pianists who have exceeded Evans's impact in shaping, and not simply preserving, the world of jazz music. But that is characteristic of Evans himself, a complex set of contradictions: someone who was one of the most gifted musicians ever to play jazz piano who also resorted to heroin as a way to cope with his insecurities as a performer, and someone responsible for bringing so much beauty into the world who at the same time lived an emotionally isolated, self-absorbed existence that brought pain and hardship to many of those closest to him. To his credit, Spiegel captures these tensions powerfully, while still ensuring that Evans's musical accomplishments remain at the forefront of our consideration of this superlative artist.

Eight years in the making, and with over 40 interviews of musicians, friends and family members, Spiegel's documentary is a comprehensive journey from Evans's boyhood in North Plainfield, New Jersey to his death at age 51 in 1980. We learn about his close connection with his older brother, Harry, who also studied music and was a capable pianist who ended up becoming a music teacher; his long-term relationship with Ellaine Schultz, who became his common-law wife for 12 years during some of his most prolific years in the 1960s and early 70s; and his gradual decline as the 1970s wore on, due largely to his persistent difficulties with substance abuse. Family members Pat Evans (Bill's sister-in-law) and Debby Evans (his niece) provide a good deal of the insight into Bill's personal life, giving us an opportunity to learn about the man behind the music.

But of course for fans of Evans, it's really the music that will be most important, and Spiegel doesn't disappoint in that regard. Evans's decision to join his brother Harry as a music student at Southeastern Louisiana University in the late 1940s would prove transformative in exposing him to music theory and classical composition, and in helping him to develop his own voice. Drummer Paul Motian, whose interview with Spiegel is one of the highlights of the film, sheds light not only on his work with Evans in the seminal trio with bassist Scott LaFaro, but his first experience in playing with him in New York in the mid-50s with clarinetist Tony Scott. Bassist Connie Atkinson discusses his work with Evans even earlier, as they played together in big bands doing "Tuxedo gigs" in dinner clubs; Atkinson would go on to become the bassist in Evans's first piano trio.

All of this was before Evans's big break with Miles Davis in 1958, as he became part of the band that would increase his visibility and forge a partnership that would result in Evans's participation in making Kind of Blue in 1959. Fittingly, this record is given extensive commentary in the film, both for its own significance and for the role it played in cementing Evans's legacy: in his interview for the film, author Ashley Khan credits Evans as the central creative force (along with Miles himself) of that masterpiece. The trio with Motian and LaFaro which produced the landmark recordings Sunday at the Village Vanguard and Waltz for Debby is also covered heavily, and it is a delight to encounter the creative process behind those magnificent records. The film's discussion of the amazing talent LaFaro brought to that trio is a particular revelation: when Gary Peacock describes his astonishment at first hearing LaFaro it is eye-opening, to say the least.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

Chicago Reader (Chicago Sun Times)

April 13, 2016

Few jazz pianists had Bill Evans's touch: his distinct sound was both resonant and delicate. Influenced equally by Bach and Bud Powell, Evans created an elegant, fluid, frequently introspective style that was unusual during the post- and hard-bop eras; he strongly influenced the development of modal jazz, particularly Miles Davis's Kind of Blue (to which he contributed as a player and writer). As smooth as Evans's music could be, his personal life was turbulent: he was a junkie, his drug addiction alienated him from his children, and both his common-law wife of many years and his schizophrenic brother committed suicide. Director Bruce Spiegel hits all the right notes of this sad song, condensing Evans's biography and conveying his significance in a snappy narrative. With Tony Bennett, Jack DeJohnette, Orrin Keepnews, Paul Motian.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

Nick Allen

Roger Ebert Film Critics

April 13, 2016

BILL EVANS: TIME REMEMBERED: “Bill Evans: Time Remembered” is a sophisticated doc with grade-A storytelling, overcoming any dusty video quality with an exhilarating focus on a fascinating life. Director Bruce Spiegel’s doc is a story of a genius, the jazz pianist and composer Bill Evans, and how he rose from a type of prodigy to a wonder of the genre, especially as a key collaborator with Miles Davis on the likes of “Kind of Blue.” Evans’ tragedies are expressed with delicate filmmaking, enlivened by personal talking heads who all seem to be sitting in their homes during the interviews (a warming homemade touch among many). Like the best of music docs, it never hesitates to dissect the great technical qualities of Evans, or to paint a picture of the jazz scene that’s wider than just one brush stroke. Along with being a full, emotional portrait as intimate as a friendly conversation, it is jazz geekery unleashed, the type of feature-length ode that you can only find at venues like CIMMFest.

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬

Scott Pfeiffer

The Moving World

April 13, 2016

This is a pleasure for jazz aficionados, a stirring, haunting film devoted to the great pianist/composer. As one rememberer puts it, Bill Evans, hunched over in communion with his contemplative, dreamlike piano, told stories in his playing. Particular catnip for connoisseurs: the sections covering Evans's time playing with the Miles Davis Sextet, particularly the worldhistoric, cool-walkin' "Kind of Blue" sessions in 1959. We hear the beautiful "Flamenco Sketches," based around Evans' signature modal sound (it's based on his "Peace Piece"). Like Satie, this music somehow feels both still and in motion at once, evoking time and space, the turning of the earth. Particularly well-selected photographs capture the jovial spirit of Cannonball Adderly one hears in the grooves of "Kind of Blue." Photographs of Evans's girlfriend Peri Cousins, for whom he wrote "Peri's Scope," are as vivid and unforgettable as stills of a Golden Age actress. We also get glimpses of the storied days of the Bill Evans Trio, with bassist Scott Lafaro and drummer Paul Motian, and their legendary two-week stand at the Village Vanguard in 1961. We learn about Evans's loving bond with his brother, Harry, though his story ends sadly. (Bill wrote "Waltz for Debby" for Harry's daughter Debby, who is interviewed in the film remembering her dad and her uncle). Evans's life was more marked than most by tragedy. The dapper man became a selfish junkie, while still remaining a musician's musician. Making a good music documentary is the art of editing, even more so than in most films. One must start with good interviews, then chop and stir them evocatively into good performance footage and photographs. Bruce Spiegel has made a well-turned picture in this mold. His film sings and illuminates, and we get to hear plenty of Evans's beautiful piano. Tony Bennett, interviewed in the film, calls his collaboration with Evans his favorite of his career, and leaves us with something Evans once said to him, words he tries to live by: "Search only for truth and beauty."

♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬ ♬